About the Liuto forte

Early History

- Lute and guitar – a dilemma?

- Lute and guitar in the 20th century

- Why the lute died out

- Original instruments – original sound?

- The stringing of historical lutes

- Rift between guitar and lute

- Distinctions in sound

- Methods of guitar and lute construction

- The guitar’s limited bass range

About the Liuto forte

- A Lute for the 21st century

- “Guitar-lute“ or “authentic“ lute

- Historical Liuti forti

- Single or double strings?

- Liuto forte sound

- Liuto forte stringing

- Fingertips or nails?

- The belly

- Fine tuning

- The rose

- Fixed or tied-on frets?

- Tuning pegs

- The nut

- The fingerboard

- The bridge

- Playing position

- Playing technique

- Prospects

Lute and Guitar in the Twentieth Century

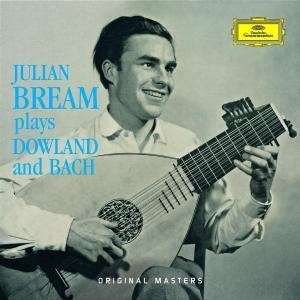

As late as the 1970s, an enthusiasm for the lute and the guitar still went hand in hand. But a growing consciousness among lutenists of their historical roots led of necessity to a disruption of this open relationship, with the result that owners and lovers of both instruments began to seriously neglect the one or the other.

Guitarist have largely abandoned Segovia’s claim to be the legitimate heirs of the Renaissance and Baroque lutenistic treasures, sadly relinquishing their share in a brilliant past. Visiting guitar festivals today, or competitions and other offerings on the instrument, one is not seldom left with the impression that this immense sacrifice of repertoire is being increasingly compensated for by a kind of narcissism in which the guitar itself and its fabulous sonic properties become sole focus. The place of compositions from the 16th to the 18th century is often taken up by program highlights emphasising a non-European or World Music flavour. These are, of course, perfectly compatible with the natural charm of the instrument and the virtuosity of its players, yet are not always a convincing support of the guitar’s original claim to “seriousness” in the Classical sense. In any event, such populistic tendencies provide an enrichment. It is undeniably due to its attitude of openness – openness to absolutely all contemporary musical styles and trends – that the guitar has established its position: a position comparable in some ways, at least in the guitar’s capacity as a solo instrument, to the pre-eminence of the lute in the 16th century.

Performers on lutes built according to historical models have familiarised audiences in recent years with the subtle charms of a forgotten art. But open and disinterested listeners will have realised anew, why it was that the instrument could not cross the threshold into the 19th century. Unimpressed by this historical fact, more than a few practitioners of “authentic“ lute playing have retained the confidence that the very high quality of the musical repertoire they cultivate is a licence to pay little or no attention to changed ideals for the cultivation of particular musical tone, or to the demands of today’s performing conditions. Trusting to ancient reports of their instrument’s marvellous effects, lutenists continue to hope that a sound, delighting hearers 300 years ago, will still call forth the same ecstatic response.

It is to be feared that there is a connection between such an attitude and the dwindling numbers of students enrolling for lute tuition. The view has been voiced, in fact, that enthusiasm for the lute in its historical version had already passed its peak by the late 1980s. This need not make us pessimistic.

Champions of historical lute performance have extraordinary and admirable achievements to their credit. The immense range of surviving repertoire for instruments of the lute family, from over 300 years of flourishing, has been only revealed thanks to their perseverance. Above and beyond this, there are players who practice their art at a level today that will be scarcely inferior to that of the great lutenists of the past.

In sum, it can be said that the imaginative efforts of lutenists, lute makers and specialists in lute music research have enabled us to discover and reconnect today – after its being broken off in the 18th century – with the glorious tradition of an irreplaceable instrument. On the other hand, the guitar and its champions receive the honour of having continued to develop the playing techniques, sound aesthetics and construction principles of plucked instruments and, at the same time, to have kept alive the memory and repertoire of their sister instrument. And it must be admitted that the late Romantic guitar as devised by Antonio de Torres (1817-1892), was no more able than the historical lute to solve the problem of a significant incompatibility of plucked instruments in the post-Baroque ensemble. The Spanish guitar remains, in spite of new sound design, in principal a solo instrument.